Pineiada, Oichalia, Farkadona

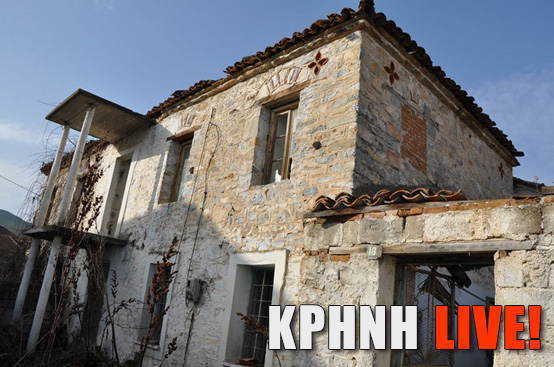

“When you see it every day, you get used to it and it doesn’t impress you” admits with a smile a resident of Pineiada who talks to us about the abandoned residence of the chiflika village. And yet, even if you get used to it, it’s definitely not something out of the ordinary. In fact, it is a wonderful stone building from the beginning of the 20th century. From those that in other parts of Greece and the world are turned into luxurious agro-tourism guesthouses, leisure centers and cultural spaces, it is enough of course that the opportunities and incentives exist.

The little house of Zografos in Pineida

Looking at the house from the outside, we chat about the origin of the old name of Peniada which was “Zark-Mari”, i.e. “Zarko of Mary”, a name that according to local tradition arose when the village was given as a dowry to the prosperous bride Maria, his daughter local farmhouse of Zografou.

However, the historical information reveals that the original name of Piniada is simply “Maria” in honor of the daughter of the Painter, while it was later renamed to Zark-Marie as it belonged to the community of Zarkou. And the said “dog” of the chiflika is a neat, sturdy two-story structure with a rectangular plan, structured in a way that reveals wealth, built around 1900.

The doghouse lies locked, unexploited, surrounded by natural vegetation. The external stone staircase and the balcony to which it would lead have been destroyed. Although it has suffered the wear and tear of time, the newer tiled roof gives the whole complex an imposing appearance in combination with the spacious plot.

In the yard agricultural machinery of our time rests waiting to be put to use. The mountain opposite does not shade it at any time of the day as it is north of the building. On the opposite side of the road, a short distance away, the stone primary school of Peniada is talking to the dog.

An inevitable comparison of the main building with the caretaker’s house, a small outbuilding next to the large two-story one, further enhances the sense of richness in the construction methods, turning the hut into a living imprint of the hard reality on the architecture.

A reality where the rich plain was worked by the collies and the profits reaped by the farmers. And this perhaps constitutes a distant encyclopedic information without familiar images for the students who have heard about the chiflikias from the school books with the references to the attitude of Killeler and the short story “To Burini” by the great M. Karagatsis. And yet, similar to the way that the seaman’s profession is a family tradition for a barren Greek island, the homesteaders and the koligi are living history for the Thessalian plain.

The villages of this place have to remember that the profession of the farmer in modern Greece was never sufficiently rewarded, let alone that it was always a means of cruel exploitation.

The house of Zografos in Oichalia

In Oichalia, or Neohori, a farm belonging to Ali Pasha Tepelenlis during the Turkish rule, we find a twin house, the Sakellariou house, also locked at the main entrance. And we call it a “twin” because it shares basic characteristics with Zografou’s dog in Pineida. As the folk houses of the area are either elongated single-story or clearly smaller two-story, modest, with rough masonry and limited spaces, it becomes obvious that this house also belonged to some important person of the village.

A little literature research verifies the obvious. “The sultan granted the estate to an official and he sold it to Christakis Zografos in 1875.

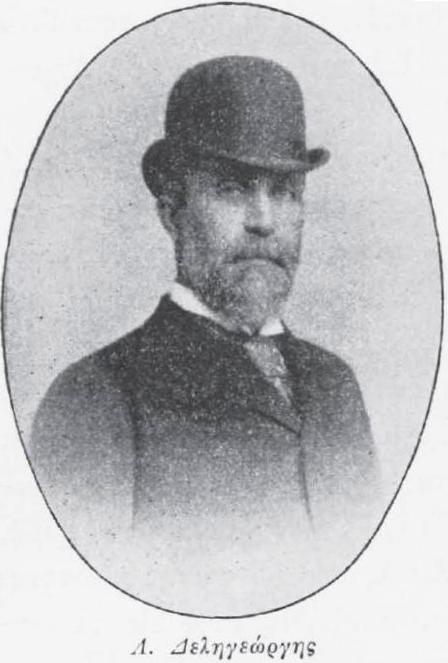

Christakis Zografos gave it as a dowry to his daughter Theanos, wife of Leonidas Deligiorgis (Minister of Foreign Affairs of Greece – Period 24 October 1890 – 18 February 1892).

The residence of Deliiorgis, approximately 90 years old (in 1992), is preserved in good condition, three-storey, stone-built, and with a tiled roof (the kutcheki). {3}

Although reminiscent of the dowry of “Maria” in Pineias, this house that was given as a dowry to Theano is surrounded by a more densely structured fabric as it is located in the center of Oichalia. It does not allow you to stand at a distance to observe it.

The wall forces you to walk through the surrounding alleys in order to see all sides of it. You discover that the house is not strictly rectangular, but in the rear view it forms projections and additions, the most modern of which appears to be a residential wing that “rests” on top of the inhabited building and shares the same yard as the dog house. Part of the ground floor is also inhabited and shines with cleanliness.

The house of Athanasiou Palioura in Farkadona

We leave Oichalia- or Neochori, and we now come to Farkadona where the scenery changes. Here there is the feeling of the center, the density of the buildings has something suffocating in relation to the loose construction in the previous villages. Yards are limited. It seems that there was an attempt by the buildings to offer defense in the past and this is not easily erased from the form of the urban fabric. Because the trace of the consolidated original fabric is usually altered due to some massive disaster that did not happen here, such as fire, earthquake, countervailing.

We are looking for a building that is different from the others. But in Farkadona we do not search randomly. We have in mind a little gem in the capital city. It is a preserved ground floor house of 1930 with elaborately landscaped surroundings. Its history: it belonged to Mr. Dimitrakopoulos Kon/nos, with the current owner being his grandson Mr. Thanasis Palioura, a retired engineer, under whose care it was renovated in 1994. It is the home of a man who knows how to appreciate the genuine, the authentic, that which carries memories. That’s why he equipped it with love.

The main facade on the road in the color of ocher is plastered and does not reveal its stonework like the rest of the building while it has been invested with a classicist mantle. Colors, cornices, window frames and other details change the appearance of the architecture and remind us of the district of Plaka in Athens. We could say that it imitates the eclectic mantle that the existing buildings throughout Greece were clothed with to such an extent in search of the romance of classicism that became this tendency part of the history of architecture.

Mrs. Debora Oikonomoula opens the front door for us and we walk parallel to the house to find ourselves in the yard and the secondary entrance. The yard is a dream setting consisting of auxiliary buildings of a few square meters alternating with free planted spaces and ornamental plants. Small corners are decorated with well-preserved objects of the past: the cart, the tap, the ceramic jar create small themes in the yard.

The house includes 4 bedrooms, the main corridor and the auxiliary spaces, bathroom and kitchen. We are won over by the flower-patterned murals inside these spacious rooms. The household equipment of the house consists of original objects and furniture from the previous century, creating a complete set, worthy of a small folklore museum and taking us to another era. Floors, fixtures and plasterwork have been retained with some limited additions necessary for modern living.

Keramidi, Panagitsa, Grizano, Diasello

Talking in parallel about an architecture “unknown” happens when you finally realize how little you actually knew about the roots and true value of that architecture, even though its image is so familiar to you.

In the villages of Farkadona, the traditional architecture from the small house to the stone bridge seems to repeat itself. Traditional constructions like descendants of the same family share the materials, construction method, principles and physiognomy even when they have been built centuries apart.

These “blood ties” between constructions are mainly due to the fact that before the industrialization of building technology the constructions of a place were predominantly defined by “where” rather than “when” or “who”. In the villages of Farkadona, the architecture is also defined by the climate, the plain, the rivers and the local limestone. The common needs and the uniform geophysical background essentially established the guidelines for each construction. And although the majority of the craftsmen were not local but belonged to itinerant packs from Epirus, they built in a similar way. After all, part of the craftsmen’s training was to adapt their construction to the space and climate of each region, to the available materials and local tradition[1]. This is how it happens in the Greek villages of the previous century that the traditional structures are grouped morphologically and structurally by region, and we can talk about the architecture of the villages of Farkadona.

Don’t look for these qualities in the apartment buildings of the Greek cities of the 1980s. It is bittersweet to realize that the contract apartment buildings are the same in any Greek city you find yourself. Mountainous, plain, island cities with identical apartment buildings without any noticeable difference because in the decades of compensation and construction orgasm, the only thing that counted in the end was “how much” and “how fast”.

In Keramidi, Farkadona, Grizano, fortunately or unfortunately, time stopped. The examples of traditional architecture are numerous and admirable. The houses are self-assembling. By looking at the owner’s inscription on the corner we are informed about the time of construction and learn the initials of the owner’s name. The corner or corner stone is marked many times in duplicate, with the dates marking the beginning and end of construction while the point of the cross undertakes to exorcise evil by keeping it out of the newly built house.

Of course, such elements do not survive in all houses. Especially on the plastered facades, the insistence on hygiene rules and the care of the facade covered the engraved inscriptions with successive layers of lime. Whether hewn or “carried” from the river, limestone stones as the only building material in abundance in the area were the first building material in use in every era, equally in small projects and the most important projects of large dimensions.